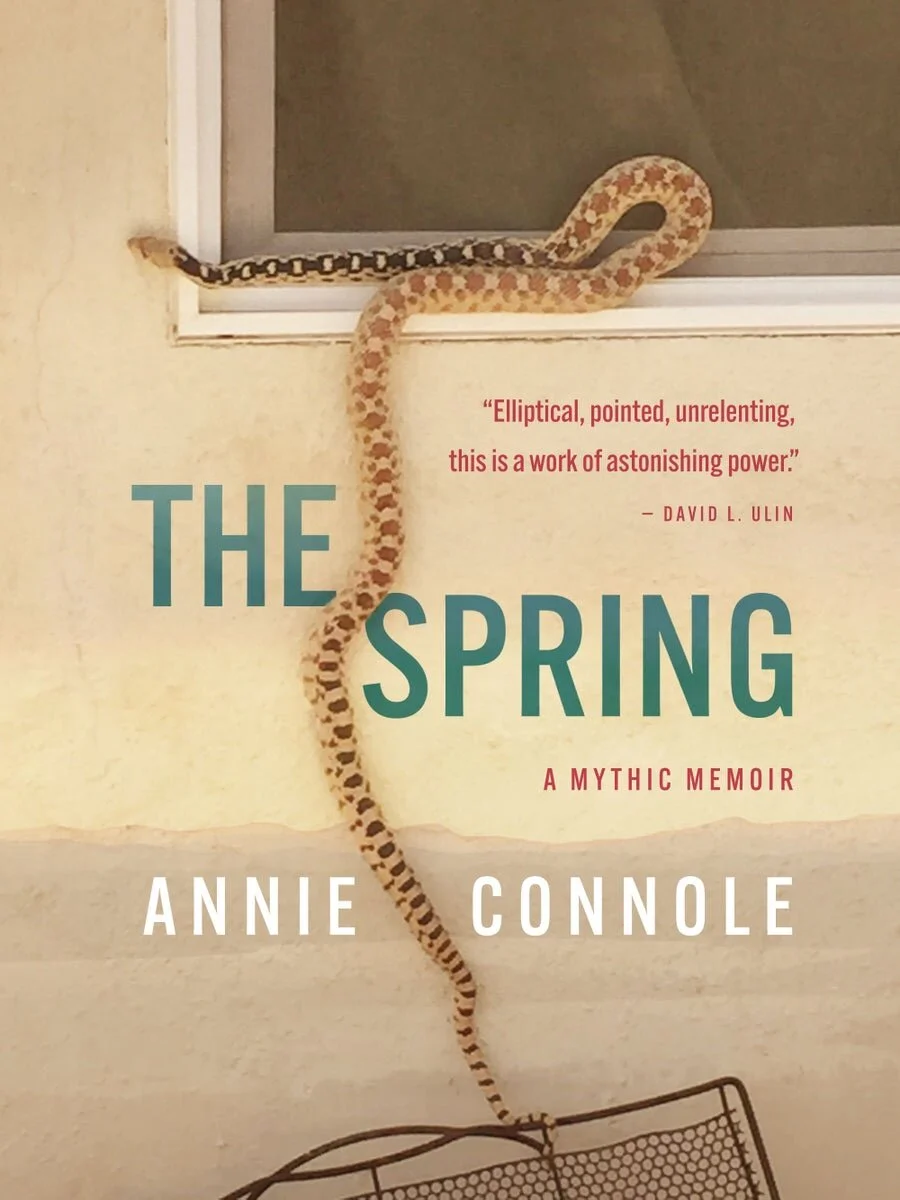

Annie Connole’s

The Spring: A Mythic Memoir

Reviewed by Rick Newby

Chin Music Press, 2021

Hardcover, $19.95

Every natural fact is a symbol of some spiritual fact.

—Ralph Waldo Emerson, “Nature”

With this remarkable first book, writer Annie Connole, Montana born and raised, brings us a work of surpassing grace, tenderness, and power. The Spring is truly a book of the West, but unlike so many texts within the western and specifically Montana narrative tradition, it relies not upon a gritty realism, but rather speaks out of an inclusive sense of the Real, one that embraces our dreams, the rich array of animals with whom we share this western landscape, and the spirits of both the living and the dead. Though it is subtitled “A Mythic Memoir,” I prefer to think of The Spring as an extended prose poem, one that must be read in a single sitting—only in this way can we experience the full force of the text’s quietly gripping arc.

With echoes of Native American animal tales, Australian Aboriginal Dreamtime stories, and even European and American folk narratives that feature animals as co-equal residents of our world, The Spring makes little distinction between the human and animal realms. Here, the narrator and her partner, the painter, continually encounter and engage with a myriad of non-human creatures wild and domesticated. Bodies of water, too, play their roles: the spring of the title, high mountain lakes, the Missouri, Gardiner, and Lamar rivers. Beginning in the mountain town of Phillipsburg, Montana, the elliptical narrative takes us to Yellowstone National Park, briefly to New York City, and then to Joshua Tree, California, where the Mojave and Colorado deserts meet and the narrator can escape the “minefield of memory up north.”

The central action of The Spring is told quietly, simply: “[T]he painter jumps into the spring on a full moon night. I never see his face again, except in dreams. He becomes light.” The text, a fable the narrator tells herself—and us—follows her struggle to find some sort of peace after her beloved partner chooses to end his own life. No explanation is given for the painter’s choice, but perhaps, as with so many suicides, any such explanation is always partial. Instead the narrator, attended by her animal allies and mentors, haunted by memories and profound disquiet, descends into the depths of grief and then, ever so slowly, begins to heal.

It is a common enough story, but here, it is told in fresh and startling ways, and in the telling, works its themes and images deep into the reader’s mind and heart. Through indirection and disjunction, “animal communions,” dream imagery, and sheer beauty, The Spring asks us to share the narrator’s journey, connecting us to our own griefs and opening us to possibilities of redemption and solace. In working this magic, Annie Connole represents a new and compelling voice arising out of the American West.

The animals in The Spring are not just part of the scenery. Not simply emblems of some human yearning, they signal changes, they join the narrator’s journey as allies or teachers, they comfort and frighten and transform. They are absolutely central to the story, more so than any humans other than the narrator and the painter. In fact, nearly every one of the brief prose poems (that, by accretion, make up the larger narrative) has as its title an animal’s name: Snake, Deer, Mountain Lion, Frog, Cat, Horse, Owl, Swan, Old Black Dog, Tadpole, Bear, Horse, Dragonfly, Moose, Sparrow, Fox, Bluebird, Rabbit, Goat, Dove, White Alpaca, Wolf, and Buffalo.

In “Bluebird,” the narrator tells us:

For many meals, for many years, I sat across the table

from the painter. Bluebird’s royal blue coat is reminiscent

of the painter’s Mediterranean blue eyes and oxford shirt.

Like the painter’s majestic eyebrows, Bluebird’s thick

black eyebrows look as though they have been painted

on in two broad strokes. Eyebrows, thick and sleek, were

the painter’s most notable feature.

As I finish my soup, I reach out to Bluebird. He flutters

again, startled, and moves to a branch by my side. Still

watching me as I watch him.

I move through new and old tracks of Yellowstone.

Many happy returns. But on this trip, I am alone,

hunting ghosts, hunting things I cannot name, hunting

elusive silhouettes with a steady knock on the inside of

my heart drumming a low beat.

Annie Connole is a writer living in the Mojave Desert. She was born and raised in the rocky highlands of Helena, Montana. Annie received a BA from The New School where she studied art and philosophy and MFA in Creative Writing from University of California Riverside—Palm Desert. Her work has appeared in literary journals including The Rumpus.